Three marks of existence

1. Three marks of existence

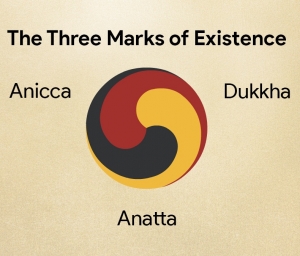

In Buddhism, the 3 marks of existence are 3 characteristics (Pāḷi: tilakkhaṇa; Sanskrit: trilakṣaṇa) of all existence and beings, namely:

- Impermanence (Anicca),

- Non-Self (Anattā)

- Suffering (Dukkha).

It is the central theme of the Buddhist Four Noble Truths and Noble Eightfold Path that humans are subject to delusion about the 3 marks of existence, that this delusion results in suffering, and that removal of that delusion results in the end of suffering.

2. Description

The 3 marks traditionally are:

- sabbe saṅkhārā aniccā —

all conditioned things are impermanent

- sabbe saṅkhārā dukkhā —

all conditioned things are unsatisfactory

- sabbe dhammā anattā —

all dharmas (conditioned or unconditioned things) are not self

In the Mahāyāna Yogācārabhūmi-Śāstra however, 4 characteristics are described instead of 3:

- impermanence (anityākāra)

- suffering (duḥkhākāra)

- emptiness (śūnyākāra)

- selflessness (anātmākāra)

In the Sūtra The Questions of the Nāga King Sāgara

these 4 marks are defined as:

- all compounded phenomena are impermanent (anitya)

- all contaminated phenomena are suffering (duḥkha)

- all phenomena are without self (anātman)

- nirvāṇa is peaceful/peace (śānta/śāntiḥ)

3. Explanation

Anicca

Impermanence (Pāḷi Anicca, Sanskrit Anitya) means that all things (saṅkhārā) are in a constant state of flux:

Buddhism states that all physical and mental events come into being and dissolve.

Human life embodies this flux in the aging process and the cycle of repeated birth and death (Saṁsāra); nothing lasts, and everything decays.

This is applicable to all beings and their environs, including beings who are reborn in Deva (God) and Nāraka (Hell) realms.

This is in contrast to Nirvāṇa, the reality that is Nicca, or knows no change, decay or death.

Dukkha

Dukkha (Sanskrit duḥkha) means unsatisfactoriness, suffering, pain

.

The Dukkha includes the physical and mental sufferings that follows each rebirth, aging, illness, dying; dissatisfaction from getting what a being wishes to avoid or not getting the desired,

and no satisfaction from Saṅkhāra dukkha, in which everything is conditioned and conditioning, or because all things are not experienced as impermanent and without any essence.

Anatta

Anatta (Anātman) refers to the doctrine of Non-Self

, that there is no unchanging, permanent Self or Soul in living beings and no abiding essence in anything or phenomena.

While Anicca and Dukkha apply to all conditioned phenomena

(saṅkhārā),

Anattā has a wider scope because it applies to all dhammas without conditioned, unconditioned

qualification.

Thus, Nirvāṇa too is a state of without Self

or Anatta.

The phrase sabbe dhamma anatta

includes within its scope each skandha (aggregate, heap) that compose any being, and the belief I am

is a mark of conceit which must be destroyed to end all dukkha.

The Anattā doctrine of Buddhism denies that there is anything called a Self in any person or anything else, and that a belief in Self is a source of Dukkha.

Some Buddhist traditions and scholars, however, interpret the Anatta doctrine to be strictly in regard to the 5 aggregates rather than a universal truth.

4. Application

In Buddhism, ignorance of (avidyā, or moha; i.e. a failure to grasp directly) the 3 marks of existence is regarded as the first link in the overall process of Saṁsāra whereby a being is subject to repeated existences in an endless cycle of suffering.

As a consequence, dissolving that ignorance through direct insight into the 3 marks is said to bring an End to Saṁsāra and, as a result, an End to that suffering (dukkha nirodha or nirodha sacca, as described in the 3rd of the Four Noble Truths).

Gautama Buddha taught that all beings conditioned by causes (Saṅkhāra) are Impermanent (anicca) and Suffering (dukkha),

and that No-Self (anattā) characterises all dhammas, meaning there is no I

, me

, or mine

in either the conditioned or the unconditioned (i.e. Nibbāna).

The teaching of 3 marks of existence in the Pāḷi Canon is credited to the Buddha.

5. In Pyrrhonism

The Greek philosopher Pyrrho (c. 360 – c. 270 BC) travelled to India with Alexander the Great's army, spending approximately 18 months there learning Indian philosophy from the Indian Gymnosophists.

Upon returning to Greece Pyrrho founded one of the major schools of Hellenistic philosophy, Pyrrhonism, which he based on what appears to have been his interpretation of the Three marks of existence.

Pyrrho summarized his philosophy as follows:

Whoever wants to live a happy life (Eudaimonia) must consider these 3 questions:

1st, how are pragmata (ethical matters, affairs, topics) by nature?

2nd, what attitude should we adopt towards them?

3rd, what will be the outcome for those who have this attitude?

Pyrrho's answer is that:

As for pragmata they are all:

- adiaphora (undifferentiated by a logical differentia),

- astathmēta (unstable, unbalanced, not measurable),

- anepikrita (unjudged, unfixed, undecidable).

Therefore, neither our sense-perceptions nor our doxai (views, theories, beliefs) tell us the truth or lie; so we certainly should not rely on them.

Rather, we should be adoxastoi (without views), aklineis (uninclined toward this side or that), and akradantoi (unwavering in our refusal to choose), saying about every single one that it no more is than it is not or it both is and is not or it neither is nor is not.

Scholars have identified the 3 terms used here by Pyrrho - adiaphora, astathmēta, and anepikrita - to be nearly direct translations of anatta, dukkha, and anicca into ancient Greek