Four schools of Buddhist philosophy

To understand better Buddhist philosophy, Buddhist views and differences between different traditions and first of all between 3 Yānas –

1) Hīnayāna,

2) Mahāyāna

3) Vajrayāna

– we have to speak about their philosophy:

Generally there could be differentiated 4 schools of philosophy-

1) Vaibhāṣika,

2) Sautrāntika,

3) Yogācāra (Cittamātra in Tibetan sources)

4) Mādhyamika

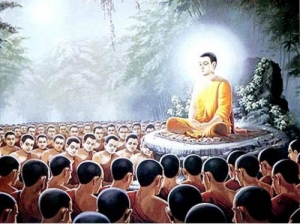

All of them are based upon Buddha Śākyamuni teachings, Sūtras and Abhidharma, and may share many common terminology and views, but they are quite different how far in their deductions, conclusions, definitions and practice they may go.

Generally it is considered:

a) Vaibhāṣika and Sautrāntika represent philosophical views of Hīnayāna or Lesser Vehicle,

b) Cittamātra philosophy is the theoretical bases of Mahāyāna Buddhism and

c) Mādhyamika – philosophical foundation of Vajrayāna Buddhism.

There can be some occasional shifts like Sautrāntika – Yogācāra, which would probably correspond to some Zen schools if they would ever care about philosophy.

Tibetan Buddhism mostly is based upon philosophical schools of Cittamātra and Mādhyamika,

referencing to Cittamātra as that which describes best the relative truth understood through the eyes of ordinary Buddhists and philosophers,

while Mādhyamika philosophy is attempting to describe the indescribable – the Ultimate Truth, the truth as seen by eyes of Enlightened Buddhas.

While it would be worth to discuss each of 4 schools of philosophy at great length and detail, objective of my current article is to introduce you to some of the most important notions and tenets of each.

The views of Vaibhāṣika philosophy are based upon non-substantiality of personality

(no real self or eternal soul):

They meditate mostly on 16 aspects of four Noble Truths and impermanence of everything to liberate themselves from Saṁsāric existence.

According to their views at ultimate level everything consists of indivisible atoms of matter and indivisible moments of consciousness.

But all gross things consisting of atoms and the flow of consciousness consisting of separate moments of consciousness they consider the relative level of truth, because they don’t exist at the absolute level.

According to Vaibhāṣika philosophy - everything cognizable, including the space and 3 times, exist substantially, you can say about them – they are real things.

Everything cognizable they divide into 5 skandha or groups of elements.

They assert all cognizable things we can perceive or think in the world really existing. However they divide real things on absolute level

and real things on relative level

:

Real things of absolute level could be divided to 3 categories:

1. Forms

2. Mind (Mind and mental events that accompany it.)

3. Formational factors.

Sautrāntika share most philosophical views and meditation methods on non-substantiality of self

with Vaibhāṣika. But there are a few other philosophical disagreements though:

Vaibhāṣika considers the Time really existing or substantially existing:

For that reason they consider absolutely existing not only indivisible moments of consciousness and indivisible particles of matter existing at present, but also those of the past and future.

Sautrāntika School of philosophy recognizes only substantial existence of indivisible particles of matter and indivisible moments of consciousness of the present:

They deny the real existence of Time and Space and for this reason also reality of past and future. Sautrāntika also deny a substantial existence of Formational factors.

But they still consider dharmas of Form and Mind really existing.

Cittamātra (Yogācāra) philosophy denies real existence of indivisible atoms of matter and indivisible moments of consciousness:

All that Sautrāntika considers really existing on absolute level, Cittamātra considers existing only on relative level.

On absolute level only Mind exists:

The Mind can be characterised by clarity (ability to manifest) and awareness.

It is also impermanent and exists moment by moment, but this clear and self-aware mind is not divided to object of perception and the moment of mind perceiving it.

This clear Mind manifests all reality out of itself and is aware of it.

According to Cittamātra all beings and Buddhas alike possess this all-pervading indivisible Mind, called ālaya-vijñāna from what everything arises.

Only due to our delusions and obscuration we often don’t recognize it is Our Mind and it’s wisdoms that are manifested and it causes sufferings of sentient beings.

The main difference between Hīnayāna and Mahāyāna is that:

Hīnayāna consider and build their practice according to theory that all external objects and moments of mind have a substance and really exist, except there is no real substantial self.

While Mahāyāna philosophy considers none of them have a real existence, they are only manifestations of Mind.

According to Cittamātra philosophy if something would really exist, it would not change – it would only exist and exist and could not move.

It is only Mind which can bring together different impressions and perceptions and create an existing image.

Later Nāgārjuna and others developed a 4th philosophical tradition inside Buddhism – Mādhyamika:

They analysed the Cittamātra philosophy and concluded that the Mind which is pervading everything – Ālaya-vijñāna – also cannot have a substantial existence:

The Mind was defined as that what is aware of its object

, but if the object of mind is not real, the mind recognizing it cannot be really existing:

If there is no object, there is no consciousness.

Mādhyamika denied also real existence of the present time,

- if there is no really existing past and future, there can’t be also a really existing present, because it is just a dot between now non-existing past and non-existing future.

Mādhyamika philosophy considered all statements regardless if it’s done by Buddhists or non-Buddhists regarding existence or non-existence cannot describe the Ultimate Truth, which exist before any words, notions, descriptions or judgments.

Mādhyamika is the central doctrine of Vajrayāna Buddhism.