Monasticism in Buddhism

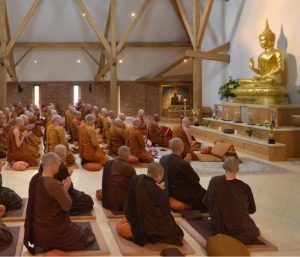

1. Monasticism in Buddhism

The term monasticism is derived from the Greek word monos, which means “single” or “alone.” Despite the etymology, the majority of Buddhist monastics are not hermits or solitary wanderers.

Monastics, even those who may choose to take up a solitary life from time to time, belong to the Buddhist Saṅgha or community.

The range of Buddhist monastic communities is quite extensive:

including everything from extremely large and wealthy urban monasteries, to mid-size and small village monasteries, to forest, cave, and mountain monasteries.

Buddhist monasticism has its origins in India and dates back to the lifetime of Śākyamuni Buddha:

The earliest members of the monastic order appear to have led lives that alternated between wandering from place to place in groups and residing in parks and groves donated by kings and wealthy merchants.

Some Buddhist scholars have argued that the wandering lifestyle was gradually transformed into a more permanently settled monastic existence as a result of the Buddha’s requirement that monks and nuns cease wandering during the monsoon season.

Other Buddhist scholars have argued that the first monastic complexes were the result of the desire of wealthy laypeople to donate land and permanent structures to the Saṅgha.

Although scholars debate the origins of monasteries,

they do agree that with the advent of permanent structures, there arose a class of monastics who remained in the monasteries permanently to act as caretakers and administrators.

Texts and archeological evidence reveal that shortly after the death of the Buddha, there were 18 large Buddhist monasteries near the city of Rājagriha alone.

The records of Chinese Buddhist pilgrims point to the existence, during the 5-7th century C.E., of great Buddhist monasteries and monastic universities in India that housed thousands of monastics from a variety of Buddhist traditions.

The monasteries quickly became wealthy institutions endowed with land, buildings, and numerous possessions.

The Buddhist monastic order was originally made up of ordained male and female monastics.

During the medieval period, however, the lineage of fully ordained nuns died out in the Theravāda order. Although the formal order was gone, some women did continue to live as novices in nunneries.

While novice nuns in certain countries often lack the recognition and support that is so essential to their survival, novice nuns in other countries (such as the Śrāmaṇerikā in Tibet) have enjoyed a wider network of support and a greater recognition of their status.

Since the 1980s there have been moves to reintroduce the lineage of fully ordained nuns in certain Theravada countries such as Śrī Lanka and Thailand, though this effort has often met fierce opposition from the male order.

By the medieval period all Buddhist monastic orders had died out in India. By that time, Buddhist monasticism had already become a pan-Asian phenomenon.

Within the last century Buddhist monastic institutions have not only been reestablished in India, but have also been founded throughout North and South America, Africa, Europe, and Australia.

2. Monasticism and the Saṅgha

In Buddhism, the monastic order is referred to as the Saṅgha, which, in its strictest sense, refers specifically to Monks and Nuns.

The Saṅgha began when the Buddha accepted his first 5 disciples shortly after his Enlightenment.

As the monastic order grew and the religion spread in an ever-widening radius, numerous disciplinary rules were put forth to govern the lives of the monks and nuns.

Even though the rules, which are found in the Vinaya section of the Buddhist Canon, are very complex, the underlying intention is straightforward: to help guide the lives of monks and nuns on a spiritual Path and to create a unified group of monastics.

The Buddhist monastic order functions to preserve and teach the Buddhist doctrine and, by dictating how to live in accordance with the way taught by Śākyamuni Buddha, the order’s rules provide an historical link to the past.

The Buddha originally functioned as the head of the monastic order.

At the time of his death he refused to appoint a successor; instead, the Buddhist teachings and disciplinary code were said to take the place of a central authority.

Lacking a leader who could maintain doctrinal and disciplinary congruity, the Saṅgha split into several monastic traditions in the centuries following the death of the Buddha.

The early splits in the Saṅgha were often based on disputes regarding discipline and led to the formation of separate Vinaya texts.

Within the first millennium following the death of the Buddha and continuing to the present, the disputes often related to doctrinal and disciplinary issues, thus resulting in the growth of Buddhist sects and schools centered around particular doctrines, texts, monastic leaders, and practices.

The lack of a central authority in Buddhism may be seen as problematic and as the cause of internal disputes and divisions.

In a more positive light, the openness to interpret Buddhist practice and doctrine has led to a staggering range of Buddhist monastic institutions and types of monastic vocations, thus contributing to the adaptation of the tradition through time and space.

As the order expanded geographically over time, adjustments were needed to make the tradition and the monastic institution acceptable to the people living in the various countries where the religion was introduced:

For example, while monks of the Theravada order (such as those living in Śrī Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia) are prohibited from farming and must receive their food directly from the laity,

the monks from the Chan School of East Asia are encouraged to grow their own food, an idea that is closely related to the Confucian ideal of not being a parasite to society.

3. Categories of monastics

Buddhist monasteries house many different categories of Buddhist monastics, from postulants seeking admission into the Saṅgha to the abbot of a monastery.

Prior to becoming a monk or nun, a person seeking admission into the Saṅgha usually spends a probationary period, ranging from several days to several years, in the monastery where he or she is seeking Ordination:

During this period, the postulant learns about the practice of monastic life, is involved in various menial and demanding tasks around the monastery, and is in charge of taking care of the needs of the other monastics.

This period allows the postulant as well as the monks and nuns of the monastery to ascertain whether monastic life is an appropriate choice.

Traditionally, entrance into the Buddhist Saṅgha follows a 2-step process in which the postulant first becomes a novice (Śrāmaṇera, Śrāmaṇerikā) before becoming a fully ordained monk (Bhikṣu) or nun (Bhikṣunī).

To become a novice, one must be old enough to scare away crows (usually interpreted to be 7-8 years of age).

Novices must follow 10 basic injunctions or Precepts:

1. Not killing

2. Not stealing

3. Not engaging in sexual activity

4. Not lying

5. Not taking intoxicants

6. Not eating after midday

7. Not watching shows or listening to musical performances

8. Not wearing garlands or perfume

9. Not sleeping on high beds

10. Not handling gold or silver (understood to be money)

Monks and nuns who remain in the order may choose, once they reach 20 years of age, to take a second, more formal “higher” ordination (upasampadā):

As “fully ordained” monastics, monks and nuns are required to follow a greater number of precepts that not only elaborate the 10 novice precepts, but also deal with subjects of decorum, dress, and demeanor.

Even though the number of precepts differ between the various regions and schools as determined by the Vinaya code that is followed,

monastics rarely follow all of the precepts, and in some traditions in Japan and Tibet, for example, a married clergy was deemed acceptable and even preferable.

The categories of monks and the stages of ordination outlined above are often traced back to Indian Buddhist practices.

In actuality, many variations exist regarding ordination and the categories of monastics:

One such variation pertains to whether or not becoming a fully ordained monastic is a permanent or temporary commitment.

Another important variation concerns the upasampadā ordination:

While in most Theravada countries there are social pressures for novices to take the upasampadā ordination once they reach the appropriate age,

the majority of monks in China choose to remain novices, possibly due originally to a lack of monasteries able to administer the monastic precepts.

Moreover, most East Asian monastics, after becoming fully ordained, take another set of precepts called Bodhisattva vows derived from the Brahma’s Net Sūtra, which, in accordance with the Mahāyāna tradition, are based on a commitment to lead all beings to Enlightenment.

4. Daily monastic routines

Monastic daily routines are often centered around 4 types of activities:

1) studying,

2) practicing Meditation,

3) performing Rituals, and

4) fulfilling assigned monastery duties.

Outside of these activities, Buddhist monastics have also involved themselves, from time to time, in politics and in social service activities like the construction of shelters for the homeless, schools, animal shelters, and hospitals.

Generally, daily monastic routines include activities such as:

cleaning the monastery; performing a variety of monastery duties; honoring the Buddha, his teachings (dharma), the monastic community (Saṅgha), and one’s own teacher; studying; chanting; and meditating.

In addition to being restricted by the monastic code, the daily monastic routines are further limited by the actual Buddhist tradition, monastery, rank of the monastic, and time of the year:

For instance, while certain meditation-oriented monasteries might dedicate the majority of the day to the practice of meditation, the daily routine of other monasteries might focus more heavily on studying Buddhist texts and performing rituals.

In addition to these differences, monastic routines vary between Buddhist traditions and countries:

Whereas Theravada monks from Thailand, Myanmar (Burma), or Laos might go out in the early morning to collect alms and must refrain from eating after midday,

Mahāyāna monks from China, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan rarely seek alms and may partake in an evening meal (sometimes called a “medicine meal”).

Daily monastic routines may also change depending upon the time of year:

For example, whereas monks living in certain Son (Chinese, Chan) monasteries in Korea might meditate for over 14 hours a day during the retreat seasons (summer and winter),

they may devote little time to meditation during the non-retreat season:

During this time, monks often visit other monasteries, travel on PILGRIMAGES, and engage in various other projects around the monastery, such as gardening, farming, and construction work.

Buddhist monastic routines are also punctuated by monthly rituals and ceremonies that may vary in form and content between the different Buddhist traditions:

One such monthly ritual commonly practiced in the Theravada tradition is the poṣadha (Pāli, uposatha) ritual, which is held semi-monthly on New Moon and Full Moon days:

In this ritual, the disciplinary code is recited and the members of the monastic community are asked whether or not they have broken any of the precepts:

This confessional ritual creates a sense of unity within the monastic community and encourages self-scrutiny and monastic purity, which are necessary for spiritual progress.

The poṣadha ritual is slowly gaining in renewed popularity in certain Mahāyāna countries such as Taiwan and Korea.

In monasteries where the ritual is not practiced, other monthly and semimonthly rituals may take its place:

It is common in the Korean Son tradition, for instance, that every fortnight during the New and Full Moons days the abbot gives a lecture and may even administer the Bodhisattva precepts to the monks:

Usually this lecture covers various aspects of the Buddha’s or other famous Buddhist monks’ teachings, as well as brief instructions on meditation.

Yearly rituals and celebrations also play an important role in monastic routines:

One of the most popular and important annual Buddhist ceremonies is the celebration of the Buddha’s birth, Enlightenment, and Death. This ceremony usually occurs during the Full Moon of the 4th lunar month (usually late April or early May) of each year:

In anticipation of this very important celebration, monks in the week leading up to the Full Moon begin thoroughly cleaning the monastery and decorating it with handmade paper lanterns.

During this ritual, the laity flock to their local monastery,

where they wander in and around the monastic buildings, meet with the monks and nuns, partake in certain rituals, and attend lectures on various aspects of the Buddha’s life and teachings.

5. Monks and laity

The survival of the Buddhist monastic order depends on 2 factors:

a) men and women who desire to take up the monastic life and

b) the Laity who support them.

From the earliest period, it was the laity who funded the construction of the first Buddhist monasteries in India and beyond.

Despite the fact that a monastic “goes forth” (pravrājita) from society when he or she enters the Saṅgha, monks and nuns remain deeply connected to the laity in a symbiotic manner:

The laity ideally supplies the 4 requisites (food, clothing, shelter, and medicine) to the monks and nuns in exchange for guidance and spiritual support in the form of sermons and the performance of rituals.

The interaction between monastics and the laity varies considerably depending on the type of monastery:

Whereas residents of forest, cave, and mountain monasteries tend to have more limited contact with the laity, monastics living in village and city monasteries often have close ties with the laity.

Indeed, along with serving as centers where the laity could receive instructions on Buddhist doctrine and practices, these urban and village monasteries functioned and may still function as educational centers that teach religious and secular subjects.

Underlying the symbiotic relationship between the monastic order and the laity is the very important concept of merit:

As the monastic order is made up of people who represent, perpetuate, and follow the teachings of the Buddha, the monastic institution itself is said to be the highest field of merit and therefore most worthy of offerings:

According to this system, donating to the monastic order is one of the most wholesome acts a person can perform and anything donated to the Saṅgha increases the donor’s store of merit:

Not only does this merit ensure good fortune and more propitious rebirths in the future, it can also be transferred to others who need it, such as a deceased relative.